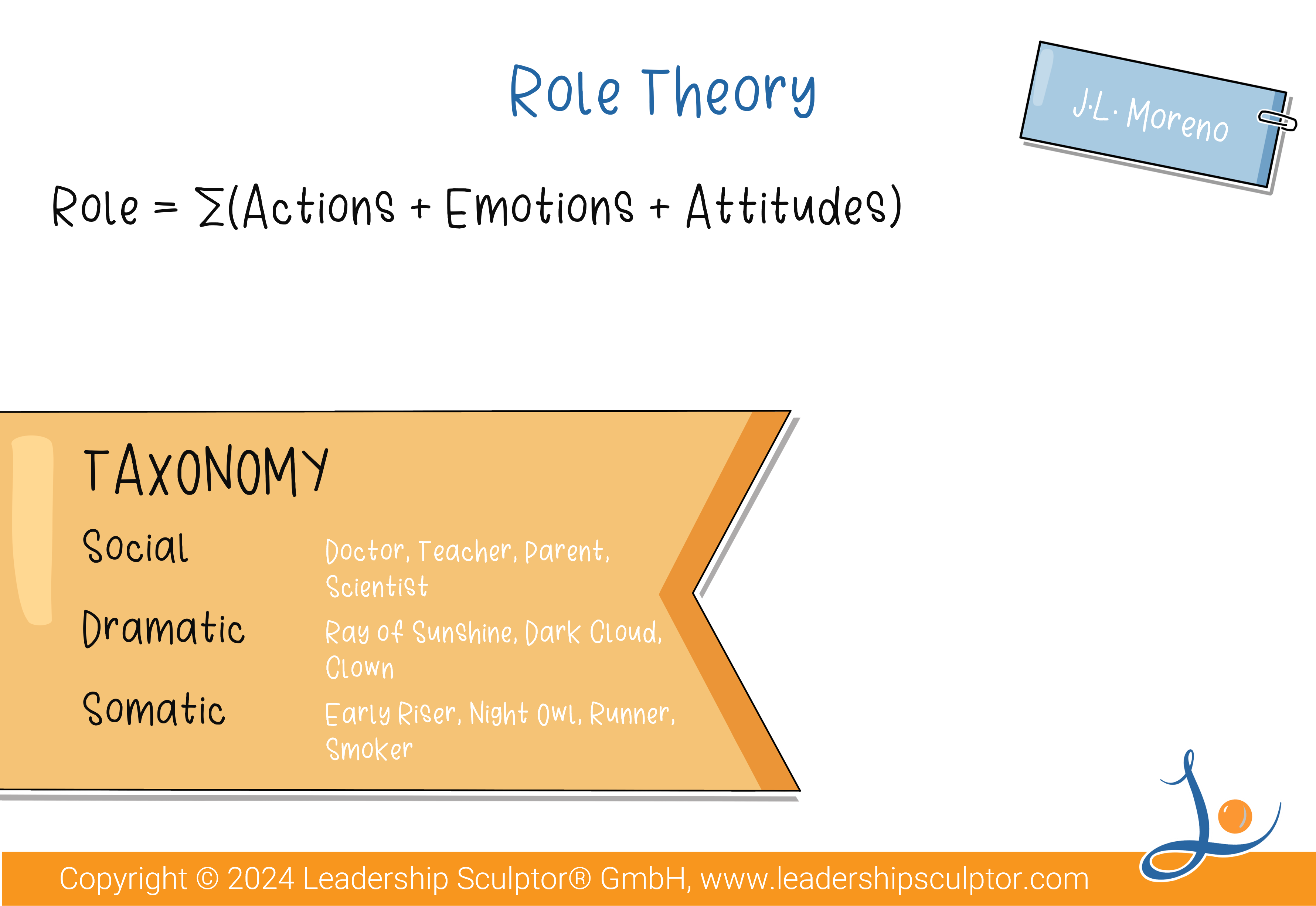

We all take on different roles in our daily lives, whether as leaders, team members, or friends. Understanding these roles and how they shape our behaviour is essential for effective leadership and meaningful interactions. Dr. Jacob L. Moreno introduced a taxonomy that organises roles into three categories: social, dramatic, and somatic. This structure helps us make sense of the complex ways we engage with the world and the people around us.

Social roles are the ones we are most familiar with. They are based on shared societal understandings of what the role entails. Think about roles like doctor, teacher, parent, or scientist. If you asked a group of people what they expect from a doctor, most would come up with a similar list that would contain tasks such as data analysis, diagnostics, prescription, and patient conversation. These shared expectations provide consistency and clarity in our interactions, making social roles a foundation for navigating relationships and responsibilities.

On the other hand, dramatic roles bring in the element of personality. While social roles define expectations, dramatic roles reveal how we approach those expectations. For example, not all doctors perform their roles in the same way. One might bring warmth and optimism, acting as a “ray of sunshine,” while another might approach their patients with caution and a focus on risks, embodying a “dark cloud.” This blend of social and dramatic roles allows us to adapt and personalise how we fulfil our responsibilities. It also helps explain why two people in the same role can leave such different impressions.

The third category, somatic roles, comes from the Greek word “soma,” meaning body. These roles reflect how we manage our physical needs and habits, such as being an early riser, a night owl, or someone who thrives on regular exercise. In a leadership context, recognising somatic roles can be particularly valuable. For example, if a team member starts expressing more of their somatic roles — taking frequent breaks or appearing unusually fatigued — it could signal stress. As leaders, noticing these shifts provides an opportunity to offer support, helping individuals address underlying issues and return to their usual productivity and well-being.

Moreno’s framework also highlights that roles are not just about what we do; they include the emotions and attitudes that come with them. Imagine two researchers who have both been selected to present at a prestigious conference. One feels excitement and pride at the opportunity, eager to share their work. The other feels anxiety and dread, questioning why they submitted their paper in the first place. Both perform the same role, but their emotional experiences differ vastly. This emotional dimension of roles influences not only how we perform but also how we connect with others.

Ultimately, roles are fluid, and their effectiveness depends on the situation and the people involved. A leader might need to shift from being a calming presence to providing clear guidance or setting firm boundaries, depending on what the moment and the person with whom we’re interacting demands. Developing this flexibility takes practice but can make our interactions more responsive and effective.

Moreno’s taxonomy of roles provides a lens through which we can better understand ourselves and those we work with. By recognising the interplay between social, dramatic, and somatic roles, we can navigate challenges more thoughtfully and lead with greater impact. After all, leadership is not just about fulfilling responsibilities — it’s about understanding the roles we play and how to adapt them to meet the needs of those around us.

What roles in your leadership journey do you find most challenging or rewarding?